I’ve posted in the past about The Bride Her Wedding Book (see here), a lovely little volume illustrated by John R. Neill in 1914, and published by the Reilly & Britton Co. I’ve picked up a few variations of the book since then, showing a couple different binding styles.

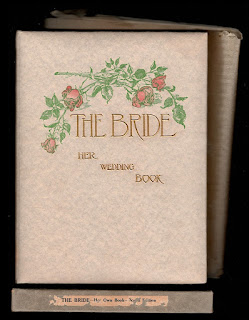

The most elaborate seems to be this, a book bound in a pictorial leatherette of some sort. The cover image of orange blossom is different from any of the other bindings I've seen, and the page edges are gilded. The blossom design is taken from a watercolor, presumably by Neill; the lettering is certainly his. This copy also includes the loose certificate that was originally inserted in the book, to be filled out by the wedding officiant.

Next up is this, sold as the “Board Edition”. This book has a padded vellum cover with a lovely drawing of roses, printed in color. This is definitely a Neill drawing - in fact they’re the same roses used on the wedding certificate - and the same lettering from the previous version is used, though in a different arrangement. This copy includes its original striped glassine dustwrapper and cardboard box. It’s interesting to note that the title on the box is The Bride Her Own Book, a slightly shortened version of the cover title. The certificate is present in this copy as well.

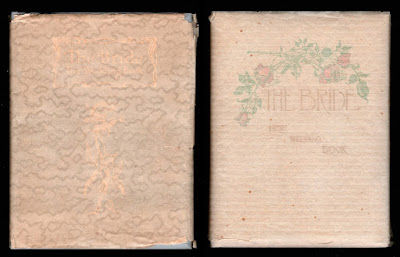

Here we have another version, this time the “Cloth Edition”. The book is bound in a fine grey cloth over beveled boards, and another new design is on the cover. This time it’s a single rose, stamped in gilt, with a re-designed title. This copy also retains its dustwrapper and box; the glassine wrapper has a moire pattern, and the box is considerably thinner due to the flat, rather than padded, covers of the book.

When the publisher changed their name to Reilly & Lee, the same basic design continued to be used. The cover is now a cream colored cloth, and the boards are no longer beveled. It’s still a lovely little book, but less luxurious, and by this time the printing of the finely detailed illustrations is a bit less sharp.

When the publisher changed their name to Reilly & Lee, the same basic design continued to be used. The cover is now a cream colored cloth, and the boards are no longer beveled. It’s still a lovely little book, but less luxurious, and by this time the printing of the finely detailed illustrations is a bit less sharp.

I believe there is at least one other variation of this cover. It appears to be bound in a glossy white textured cardboard, using the same imagery as above. The poor photo shown is from an old auction listing. With any luck I’ll run across one of these someday and learn more details!

The simple certificate that was included with the volume is shown on the right.

The simple certificate that was included with the volume is shown on the right.